Regarding the second purpose, one thing can be said with certainty about these reconstructions: they are wrong. Drawing sharp lines on a map requires more hard information than exists for these periods of time, especially for the early maps. For the later maps (660, 942), the evidence is far better and the broad outlines are certainly correct. But historians still disagree substantially on the location of some borders. Like my reconstruction using the primary sources, all that can be said is that they are no less plausible than many other reconstructions. The maps are also likely to be wrong in assuming a smaller number of states than actually existed. This is likely because in the one area where reliable records are available, Wales, the size of states was quite small. No doubt this was partly due to poor communications in mountainous terrain. Nevertheless it is likely that states outside Wales, and especially in the equally mountainous North, were smaller than those shown on the maps. It is natural that evidence for the existence of small Briton states in areas later taken over by the English would disappear. English states were quite probably smaller and more numerous as well.

The "ethnicity" of the ruling groups in these states is also sure to be more complicated than as shown in the maps. For instance, I have non-critically taken Bede's division of the English into Angles, Saxons and Jutes at face value, where others would question whether these distinctions had any meaning to the Germanic settlers in the fifth and sixth centuries. Even at the time of the last map (942), Bernicia (which I have coloured as an Angle state following Bede) was referred to as "North Saxonia" by a continental traveller.

Another anachronism in these maps is the names of states. Except for the latin names of tribes (attached to the civitates of Roman Britain), I have not necessarily labelled states using the names by which they would have been known at the time. Some names are later forms, e.g. "Gwynedd" was the much later (even than 942) form of Venedotia, first attested on a gravestone c.500. Other names are fictions of mine, e.g. "Verulam" in 530, which I have derived from its chief city, Verulamium. Others were not invented by me, but are nevertheless of doubtful authenticity, deriving from late traditions (e.g. "Theyernllwg"). Names in these last two categories, which are not well attested for any time period, I have written in italics.

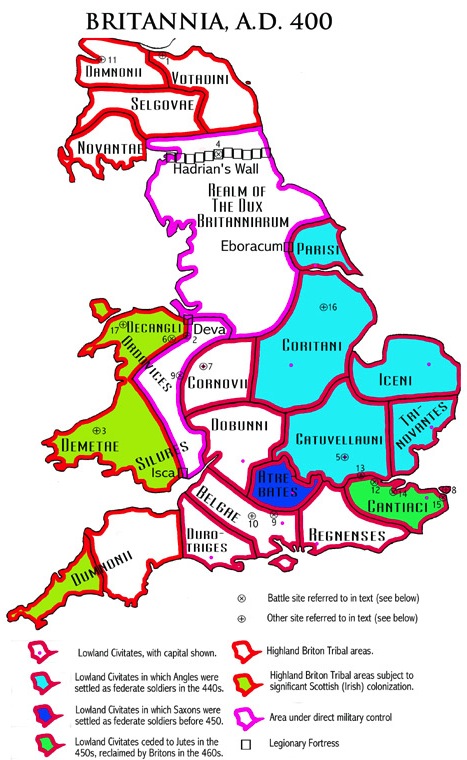

A final note: in what follows, "Britannia" refers to the area shown

on the maps. That is, the Island south of the Forth-Clyde line. This is

the area occupied by Rome and its federate allies for most of the first

four centuries A.D.

This map shows the reasonably well

established boundaries of the

civitates

(city-states) of Britannia at the end of the Roman era, as well as the

more speculative boundaries of military districts and highland tribes.

These political boundaries may have remained relatively unchanged right

up until the revolt of the English soldier-settlers (which I have

placed

in the 470s). Also shown are the states in which these Angles, Saxons

and

Jutes were settled in the 5th century as federate soldiers.

This map shows the reasonably well

established boundaries of the

civitates

(city-states) of Britannia at the end of the Roman era, as well as the

more speculative boundaries of military districts and highland tribes.

These political boundaries may have remained relatively unchanged right

up until the revolt of the English soldier-settlers (which I have

placed

in the 470s). Also shown are the states in which these Angles, Saxons

and

Jutes were settled in the 5th century as federate soldiers.

After the English

revolt, Britannia was certainly in a state of flux,

as

Gildas attests. The situation restabilized after the Britons' victory

at

Badon, which I have placed in 518. The map for 530 shows the partition

of Britain between Britons and English. This was about the time at

which

Procopius described Britain as being inhabited by three peoples:

Angles,

Frisians, and Britons, each with one king. It was also just before the

Gewissae took the Isle of Wight from the Jutes, in 530 according to the

Anglo-Saxon chronicle. Although the Britons had already lost most of

lowland

Britannia to the English, Britannia as a whole was still overwhelmingly

controlled by Britons. Also shown in this map are the possible

identities

of the kingdoms of the five kings of Gildas, (with Gwynedd split

between

Maglocunus and Cuneglasus). It can be seen that these kingdoms are the

four largest highland Briton kingdoms of Southern Britannia, and as

such

these kings may have been the chief potentates with which Gildas

(probably

located in Durotrigia) would have been concerned, in around 545.

After the English

revolt, Britannia was certainly in a state of flux,

as

Gildas attests. The situation restabilized after the Britons' victory

at

Badon, which I have placed in 518. The map for 530 shows the partition

of Britain between Britons and English. This was about the time at

which

Procopius described Britain as being inhabited by three peoples:

Angles,

Frisians, and Britons, each with one king. It was also just before the

Gewissae took the Isle of Wight from the Jutes, in 530 according to the

Anglo-Saxon chronicle. Although the Britons had already lost most of

lowland

Britannia to the English, Britannia as a whole was still overwhelmingly

controlled by Britons. Also shown in this map are the possible

identities

of the kingdoms of the five kings of Gildas, (with Gwynedd split

between

Maglocunus and Cuneglasus). It can be seen that these kingdoms are the

four largest highland Briton kingdoms of Southern Britannia, and as

such

these kings may have been the chief potentates with which Gildas

(probably

located in Durotrigia) would have been concerned, in around 545.

The political situation in

Britannia remained relatively stable for about

50 years after Badon, then changed radically in the following 20. By

585

all of the major lowland Briton states, the descendants of the Roman

civitates,

had fallen into English hands. The highland Britons were not yet

seriously

threatened, and still controlled about half of Britannia. All of the

major

Mediaeval English kingdoms had already appeared at this stage, except

for

Northumbria which had not been formed from the union of Bernicia and

Deira.

At this time, Wessex under Ceawlin was at a peak of its power, not

reached

again until the 9th century.

The political situation in

Britannia remained relatively stable for about

50 years after Badon, then changed radically in the following 20. By

585

all of the major lowland Briton states, the descendants of the Roman

civitates,

had fallen into English hands. The highland Britons were not yet

seriously

threatened, and still controlled about half of Britannia. All of the

major

Mediaeval English kingdoms had already appeared at this stage, except

for

Northumbria which had not been formed from the union of Bernicia and

Deira.

At this time, Wessex under Ceawlin was at a peak of its power, not

reached

again until the 9th century.

During the 7th century, the

English continued to advance at the expense

of the Britons. By this time (660), the Britons' political control had

been pushed back to the three Western peninsulas of Britannia: Dumnonia

(now Devon and Cornwall ), Wales, and Strathclyde-Galloway (now

South-West

Scotland). The status of Rheged is uncertain, but it was probably under

effective Northumbrian control. Shortly after this time the West Saxons

began settlement around Exeter, in the heart of Dumnonia. Nevertheless,

Cornwall was not finally absorbed by Wessex until the 10th century.

Wales

was not conquered by the English (under Norman rule) until the late

13th

century (and was even independent again, briefly, in the 15th century).

Strathclyde-Galloway was peacefully incorporated into the Scottish

kingdom

in the 11th century. Thus, 660 marks the effective end of the rapid

advance

of the English at the expense of the Britons. This time was also the

beginning

of the supremacy of Mercia among the English kingdoms. In later

centuries,

it annexed most of the smaller kingdoms, and substantial parts of

Northumbria

and Wessex as well.

During the 7th century, the

English continued to advance at the expense

of the Britons. By this time (660), the Britons' political control had

been pushed back to the three Western peninsulas of Britannia: Dumnonia

(now Devon and Cornwall ), Wales, and Strathclyde-Galloway (now

South-West

Scotland). The status of Rheged is uncertain, but it was probably under

effective Northumbrian control. Shortly after this time the West Saxons

began settlement around Exeter, in the heart of Dumnonia. Nevertheless,

Cornwall was not finally absorbed by Wessex until the 10th century.

Wales

was not conquered by the English (under Norman rule) until the late

13th

century (and was even independent again, briefly, in the 15th century).

Strathclyde-Galloway was peacefully incorporated into the Scottish

kingdom

in the 11th century. Thus, 660 marks the effective end of the rapid

advance

of the English at the expense of the Britons. This time was also the

beginning

of the supremacy of Mercia among the English kingdoms. In later

centuries,

it annexed most of the smaller kingdoms, and substantial parts of

Northumbria

and Wessex as well.

The final map, for 942, is long after

the period covered by my

narrative

of the Ruin and Conquest of Britain. I have included it primarily

because

it shows an interesting time in the history of Britain. Following the

Viking

invasions in the 9th century, the kingdom of Wessex was left as the

only

English kingdom with the power to resist. In the first three decades of

the 10th century, Wessex conquered all of the Danish, Norse, and Angle

kingdoms. But this unification of England was premature; on the death

of

king Aethelstan (939), York broke away under its Norse kings, and

doggedly

resisted reconquest during the 940s. The final transformation of the

kingdom

of Wessex into the kingdom of England (including Cornwall, but none of

Wales) was delayed until the 950s (after the death of ErikBloodaxe,

the

last king of York). The 940s are also interesting for a resurgence in

the

power of the Britons, in Strathclyde and Wales. Strathclyde under king

Donald at this time had extended southwards almost to the city of Leeds

(according to one account which seems to imply a date of c.940).

Shortly

afterwards it was peacefully annexed to the kingdom of Scotland, which

was not pushed back to its present border (north of Hadrian's wall)

until

after the Norman conquest. Wales, except for minor states in the

south-east

which were vassals of Wessex, was united under a single king: Hywel the

good. He acknowledged the king of Wessex as his overlord, but was an

independent

monarch who produced a code of law for all Wales. On his death (950),

his

kingdom was divided into three. But the idea of a single kingdom of

Wales

had taken root, and became a reality (if only temporarily) a number of

times over the subsequent centuries, right down until Owain Glyndwr in

the 15th century.

The final map, for 942, is long after

the period covered by my

narrative

of the Ruin and Conquest of Britain. I have included it primarily

because

it shows an interesting time in the history of Britain. Following the

Viking

invasions in the 9th century, the kingdom of Wessex was left as the

only

English kingdom with the power to resist. In the first three decades of

the 10th century, Wessex conquered all of the Danish, Norse, and Angle

kingdoms. But this unification of England was premature; on the death

of

king Aethelstan (939), York broke away under its Norse kings, and

doggedly

resisted reconquest during the 940s. The final transformation of the

kingdom

of Wessex into the kingdom of England (including Cornwall, but none of

Wales) was delayed until the 950s (after the death of ErikBloodaxe,

the

last king of York). The 940s are also interesting for a resurgence in

the

power of the Britons, in Strathclyde and Wales. Strathclyde under king

Donald at this time had extended southwards almost to the city of Leeds

(according to one account which seems to imply a date of c.940).

Shortly

afterwards it was peacefully annexed to the kingdom of Scotland, which

was not pushed back to its present border (north of Hadrian's wall)

until

after the Norman conquest. Wales, except for minor states in the

south-east

which were vassals of Wessex, was united under a single king: Hywel the

good. He acknowledged the king of Wessex as his overlord, but was an

independent

monarch who produced a code of law for all Wales. On his death (950),

his

kingdom was divided into three. But the idea of a single kingdom of

Wales

had taken root, and became a reality (if only temporarily) a number of

times over the subsequent centuries, right down until Owain Glyndwr in

the 15th century.